- C Landess

- 0 Comments

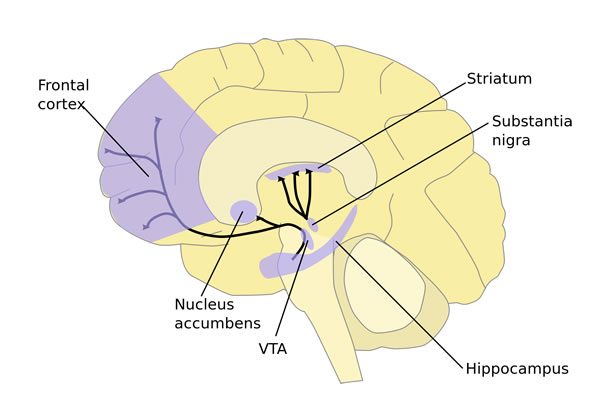

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive disorder that is caused by degeneration of nerve cells in the part of the brain called the substantia nigra, which controls movement. These nerve cells die or become impaired, losing the ability to produce an important chemical called dopamine. Studies have shown that symptoms of Parkinson’s develop in patients with an 80 percent or greater loss of dopamine-producing cells in the substantia nigra.

Normally, dopamine operates in a delicate balance with other neurotransmitters to help coordinate the millions of nerve and muscle cells involved in movement. Without enough dopamine, this balance is disrupted, resulting in tremor (trembling in the hands, arms, legs and jaw); rigidity (stiffness of the limbs); slowness of movement; and impaired balance and coordination – the hallmark symptoms of Parkinson’s.

The cause of Parkinson’s essentially remains unknown. However, theories involving oxidative damage, environmental toxins, genetic factors and accelerated aging have been discussed as potential causes for the disease. In 2005, researchers discovered a single mutation in a Parkinson’s disease gene (first identified in 1997), which is believed responsible for five percent of inherited cases.

Prevalence and Incidence

It is estimated that 60,000 new cases of Parkinson’s disease are diagnosed each year, adding to the estimated one to 1.5 million Americans who currently have the disease. There were nearly 18,000 Parkinson’s disease-related deaths in the United States in 2003. While the condition usually develops after the age of 55, the disease may affect people in their 30s and 40s.

Common Symptoms

- Tremor or the involuntary and rhythmic movements of the hands, arms, legs and jaw

- Muscle rigidity or stiffness of the limbs – most common in the arms, shoulders or neck

- Gradual loss of spontaneous movement, which often leads to decreased mental skill or reaction time, voice changes, decreased facial expression, etc.

- Gradual loss of automatic movement, which may lead to decreased blinking, decreased frequency of swallowing and drooling

- A stooped, flexed posture with bending at the elbows, knees and hips

- Unsteady walk or balance

- Depression or dementia

Diagnosis

Presently, the diagnosis of Parkinson’s is primarily based on the common symptoms outlined above. There is no X-ray or blood test that can confirm the disease. However, noninvasive diagnostic imaging, such as positron emission tomography (PET) can support a doctor’s diagnosis. Conventional methods for diagnosis include:

- The presence of two of the three primary symptoms

- The absence of other neurological signs upon examination

- No history of other possible causes of parkinsonism, such as the use of tranquilizer medications, head trauma or stroke

- Responsiveness to Parkinson’s medications, such as levodopa

Medical Treatment

The majority of Parkinson’s patients are treated with medications to relieve the symptoms of the disease. These medications work by stimulating the remaining cells in the substantia nigra to produce more dopamine (levodopa medications) or by inhibiting some of the acetylcholine that is produced (anticholinergic medications), therefore restoring the balance between the chemicals in the brain. It is very important to work closely with the doctor to devise an individualized treatment plan. Side effects vary greatly by class of medication and patient.

Levodopa

Developed more than 30 years ago, levodopa is often regarded as the gold standard of Parkinson’s therapy. Levodopa works by crossing the blood-brain barrier, the elaborate meshwork of fine blood vessels and cells that filter blood reaching the brain, where it is converted into dopamine. Since blood enzymes (called AADCs) break down most of the levodopa before it reaches the brain, levodopa is now combined with an enzyme inhibitor called carbidopa. The addition of carbidopa prevents levodopa from being metabolized in the gastroinstenal tract, liver and other tissues, allowing more of it to reach the brain. Therefore, a smaller dose of levodopa is needed to treat symptoms. This advance also helps reduce the severe nausea and vomiting often experienced as a side effect of levodopa. For most patients, levodopa reduces the symptoms of slowness, stiffness and tremor. It is especially effective for patients that have a loss of spontaneous movement and muscle rigidity. This medication, however, does not stop or slow the progression of the disease.

Levodopa is available as a standard (or immediate) release formula or a long-acting or “controlled-release” formula. Controlled release may provide a longer duration of action by increasing the time it takes for the gastrointestinal tract to absorb the medication.

Side effects may include nausea, vomiting, dry mouth and dizziness. Dyskinesias (abnormal movements) may occur as the dose is increased. In some patients, levodopa may cause confusion, hallucinations or psychosis.

Dopamine Agonists

Bromocriptine, pergolide, pramipexole and ropinirole are medications that mimic the role of chemical messengers in the brain, causing the neurons to react as they would to dopamine. They can be prescribed alone or with levodopa and may be used in the early stages of the disease or administered to lengthen the duration of effectiveness of levodopa. These medications generally have more side effects than levodopa, so that is taken into consideration before doctors prescribe dopamine agonists to patients.

Side effects may include drowsiness, nausea, vomiting, dry mouth, dizziness and feeling faint upon standing. While these symptoms are common when starting a dopamine agonist, they usually resolve over several days. In some patients, dopamine agonists may cause confusion, hallucinations or psychosis.

COMT Inhibitors

Entacapone and tolcapone are medications that are used to treat fluctuations in response to levodopa. COMT is an enzyme that metabolizes levodopa in the bloodstream. By blocking COMT, more levodopa can penetrate the brain and, in doing so, increase the effectiveness of treatment. Tolcapone is indicated only for patients whose symptoms are not adequately controlled by other medications, because of potentially serious toxic effects on the liver. Patients taking tolcapone must have their blood drawn periodically to monitor liver function.

Side effects may include diarrhea and dyskinesias.

Selegiline

This medication slows down the activity of the enzyme monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B), the enzyme that metabolizes dopamine in the brain, delaying the breakdown of naturally occurring dopamine and dopamine formed from levodopa. When taken in conjunction with levodopa, selegiline may enhance and prolong the effectiveness of levodopa.

Side effects may include heartburn, nausea, dry mouth and dizziness. Confusion, nightmares, hallucinations and headache occur less often and should be reported to the doctor.

Anticholinergic medications

Trihexyphenidyl, benztropine mesylate, biperiden HCL and procyclidine work by blocking acetylcholine, a chemical in the brain whose effects become more pronounced when dopamine levels drop. These medications are most useful in the treatment of tremor and muscle rigidity, as well as in reducing medication-induced parkinsonism. They are generally not recommended for extended use in older patients because of complications and serious side effects.

Side effects may include dry mouth, blurred vision, sedation, delirium, hallucinations, constipation and urinary retention. Confusion and hallucinations may also occur.

Amantadine

This is an antiviral medication that also helps reduce symptoms of Parkinson’s (unrelated to its antiviral components) and is often used in the early stages of the disease. It is sometimes used with an anticholinergic medication or levodopa. It may be effective in treating the jerky motions associated with Parkinson’s.

Side effects may include difficulty in concentrating, confusion, insomnia, nightmares, agitation and hallucinations. Amantadine may cause leg swelling as well as mottled skin, often on the legs.

Surgery

For many patients with Parkinson’s, medications are effective for maintaining a good quality of life. As the disorder progresses, however, some patients develop variability in their response to treatment, known as “motor fluctuations. During “on” periods, a patient may move with relative ease, often with reduced tremor and stiffness. During “off” periods, patients may have more difficulty controlling movements. Off periods may occur just prior to a patient taking their next dose of medication, and these episodes are called “wearing off.” Uncontrolled writhing movements, called dyskinesias, may result. These problems can usually be managed with changes in medications. Based upon the type and severity of symptoms, the deterioration of a patient’s quality of life and a patient’s overall health, surgery may be the next step. The benefits of surgery should always be weighed carefully against its risks, taking into consideration the patient’s symptoms and overall health.

Neurosurgeons relieve the involuntary movements of conditions like Parkinson’s by operating on the deep brain structures involved in motion control – the thalamus, globus pallidus and subthalamic nucleus. To target these clusters, neurosurgeons use a technique called stereotactic surgery. This type of surgery requires the neurosurgeon to fix a metal frame to the skull under local anesthesia. Using diagnostic imaging, the surgeon precisely locates the desired area in the brain and drills a small hole, about the size of a nickel. The surgeon may then create small lesions using high frequency radio waves within these structures or may implant a deep brain stimulating electrode, thereby helping to relieve the symptoms associated with Parkinson’s.

Pallidotomy

This procedure may be recommended for patients with aggressive Parkinson’s or for those who do not respond to medication. Pallidotomy is performed by inserting a wire probe into the globus pallidus – a very small region of the brain, measuring about a quarter inch, involved in the control of movement. Most experts believe that this region becomes hyperactive in Parkinson’s patients due to the loss of dopamine. Applying lesions to the global pallidus can help restore the balance that normal movement requires. This procedure may help eliminate medication-induced dyskinesias, tremor, muscle rigidity and gradual loss of spontaneous movement.

Thalamotomy

Thalamotomy uses radiofrequency energy currents to destroy a small, but specific portion of the thalamus. The relatively small number of patients who have disabling tremors in the hand or arm may benefit from this procedure. Thalamotomy does not help the other symptoms of Parkinson’s and is used more often and with greater benefit in patients with essential tremor, rather than Parkinson’s.

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS)

DBS offers a safer alternative to pallidotomy and thalamotomy. It utilizes small electrodes which are implanted to provide an electrical impulse to either the subthalamic nucleus of the thalamus or the globus pallidus, deep parts of the brain involved in motor function. Implantation of the electrode is guided through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and neurophysiological mapping, to pinpoint the correct location. The electrode is connected to wires that lead to an impulse generator or IPG (similar to a pacemaker) that is placed under the collarbone and beneath the skin. Patients have a controller, which allows them to turn the device on or off. The electrodes are usually placed on one side of the brain. An electrode implanted in the left side of the brain will control the symptoms on the right side of the body and vice versa. Some patients may need to have stimulators implanted on both sides of the brain.

This form of stimulation helps rebalance the control messages in the brain, thereby suppressing tremor. DBS of the subthalamic nucleus or globus pallidus may be effective in treating all of the primary motor features of Parkinson’s and may allow for significant decreases in medication doses.

Experimental Research

Embryonic stem cell research is a promising field that has created political and ethical controversy. Scientists are currently developing a number of strategies for producing dopamine neurons from human stem cells in the laboratory for transplantation into humans with Parkinson’s disease. The successful generation of an unlimited supply of dopamine neurons may offer hope for Parkinson’s patients at some point in the future.

Research currently being explored utilizes embryonic stem cells, which are undifferentiated cells derived from several day-old embryos. Most of these embryos are the product of in vitro fertilization efforts. Researchers believe that they may be able to prompt these cells, which can theoretically be manipulated into a building block of any of the body’s tissues, to replace those lost during the disease’s progression.

There is hope that adult stem cells, which are harvested from bone marrow, may be utilized in a similar way to achieve results. Fewer ethical questions surround this sort of research, but some experts believe that adult stem cells may be more difficult to work with than those from embryos. Either way, the scientific community is nearly unanimous in arguing that research efforts and potential breakthroughs will be negatively impacted if they are not allowed to work on both types of stem cells.

Human studies of so-called neurotrophic factors are also being explored. In animal studies, this family of proteins has revived dormant brain cells, caused them to produce dopamine, and prompted dramatic improvement of symptoms.

Secondary Parkinsonism

This is a disorder with symptoms similar to Parkinson’s, but caused by medication side effects, different neurodegenerative disorders, illness or brain damage. As in Parkinson’s, many common symptoms may develop, including tremor; muscle rigidity or stiffness of the limbs; gradual loss of spontaneous movement, often leading to decreased mental skill or reaction time, voice changes, or decreased facial expression; gradual loss of automatic movement, often leading to decreased blinking, decreased frequency of swallowing, and drooling; a stooped, flexed posture with bending at the elbows, knees and hips; an unsteady walk or balance; and depression or dementia. Unlike Parkinson’s, the risk of developing secondary parkinsonism may be minimized by careful medication management, particularly limiting the usage of specific types of antipsychotic medications.

Many of the medications used to treat this condition have potential side effects, so it is very important to work closely with the doctor on medication management. Unfortunately, secondary parkinsonism does not seem to respond as effectively to medical therapy as Parkinson’s.